Ever since we began transferring the criminal punishment execution

system from the Interior Ministry to the Justice Ministry, our top priority has been to

reduce the number of prisoners in correctional colonies and preliminary investigation

confinement cells-SIZOs. This problem must be solved

before we can overcome the critical situation in which the criminal executive system

currently finds itself.

Ever since we began transferring the criminal punishment execution

system from the Interior Ministry to the Justice Ministry, our top priority has been to

reduce the number of prisoners in correctional colonies and preliminary investigation

confinement cells-SIZOs. This problem must be solved

before we can overcome the critical situation in which the criminal executive system

currently finds itself.

I would like to begin by talking about why we have so many prisoners and why SIZOs are so catastrophically overcrowded. The main reason

is the criminal policy conducted in our country, and the way in which judicial and

investigation agencies perform their job. At present, investigation is bent on putting a

suspect, or person accused of a crime, in a confinement cell no matter what. The

investigator is not interested in how old this person is, what his family situation is

like, whether or not he has a job, or whether or not this is his first arrest. His

attitude is, once caught, put him behind bars. Just to be on the safe side. At present,

more than 60% of the investigators in the Russian Interior Ministry investigation

department do not have any kind of law degree. Most of these investigators are only

interested in putting a person behind bars. They believe they are fighting for a good

cause, that they are even avengers of a sort, so they have neither the time, desire, nor

training to understand the person they are dealing with. Put him in prison and everything

is alright.

Of course, the system they work under is largely responsible for this attitude, since the

quality of their work is measured by the number of crimes they expose. In Moscow, for

example, the current level of crime exposure is 92%. This is why so many people are

spending time in SIZOs for petty crimes. They are sent

there so the investigator can get another check mark and raise his crime-exposure

percentage. At the end of the month, the check marks are added up, and they say, Vanya's

done a good job, he has solved 90% of his crimes, Kolya has not done so well, he did not

quite make 60%. On the whole, I do not believe in these percentages. There are all kinds

of gangs on the prowl in Moscow, from Lyuberets, Solntsevo, etc. Why don't the police,

task-force employees, and investigators deal primarily with them?

The confinement cells in Moscow are chock-a-block. I was shocked to hear how one guy was

in a SIZO for stealing two crates of empty bottles from a

market stall! The stall keepers caught him, beat him up and handed him over to the police.

Without further ado, the police sent him to a SIZO, they

solved their crime, gave themselves a check mark, while the Lyuberets thugs continue to

run amok.

The justice minister and I paid a visit to the juvenile cell at the Chelyabinsk SIZO. I spoke to a sixteen-year-old lad.

"What are you in for?"

"I stole two bottles of vodka and a box of chocolates from a stall."

"What was the damage?"

"Eighty rubles."

"Do you have a father and mother?"

"Yes."

"Have you ever been arrested by the police before?"

"No."

"Do you have a record?"

"No."

What is the point of keeping the boy in a SIZO because of

80 rubles? I questioned another lad, this time a little tougher looking.

"What are you in for?"

"I beat up my friend."

"Why did you beat him?"

"We had an argument, we started to fight, I'm bigger than him, so he got the worst of

it."

"Have you been arrested by the police before?"

"No."

"Do you go to school?"

"Yes."

"What grade?"

"Tenth."

"How long have you been here?"

"Eight months."

Who has not been in a fight as a kid? I can also remember getting my face bashed, or being

the one to wave my fists. If this is a punishable crime, half of the men in Russia should

be in prison.

Another problem is that the number of people registered with the courts is increasing

every year. As of today, this number constitutes more than 60% of the total number of SIZO prisoners. Something must be done about the courts. The

courts are not under anyone's jurisdiction. They have become something akin to the Indian

sacred cow. They could not care less about our appeals, or about the appeals of the

prosecutors. I have discussed this problem several times with Supreme Court Chairman

Lebedev. He says, "I have no influence over the courts, they are independent . .

." Qualified colleagues have been known to deprive someone of their court powers, or

dismiss someone from their job for spending too much time on red tape, but these are

isolated cases. Yes, it is true that the courts are under-financed. But not that much

money is needed to write a sentence or make a decision on time. It all depends on the

judge's attitude to his job.

These topics should be discussed and exposed more in the mass media. Society's eyes should

be opened to the real reasons for the catastrophic situation in SIZOs and in the criminal executive system as a whole, and

shown how to eliminate them. But all we know is what we are told, our prisons are in a bad

way. They are indeed, and they will continue to be bad and may get even worse. The

government program for building new SIZOs is not being

implemented, nor is any money being allocated from the federal budget. In the past, a

little was allotted, but it was used to build barracks and warehouses. Who knows what was

actually built. Some money is allotted to the prison camp employment program. People are

given the chance to earn a little, although there are currently about 120,000 unemployed

in correctional institutions.

The situation in SIZOs is particularly serious. And here

there is little we can do. We have more rights and opportunities to influence the

situation in the colonies; there we can take advantage of provisional and early release,

and convoy prisoners. We do not have the right to do anything in SIZOs, there we only responsible for security and

surveillance. The confinement cell is under the jurisdiction of criminal procedural law.

The investigator sent a person there, and without the investigator we do not have the

right to go anywhere near him. If he has been to court, he is registered with the court,

and without the court's permission we cannot do anything, we cannot release him, or permit

him visiting hours, or allow him to receive additional parcels or packages; everything is

decided by the investigator or the judge.

At present, two norms are in effect (we pushed them through in 1995 in the "Law on

Keeping the Accused and Suspects in Custody") which give SIZO

superintendents the right to release prisoners whose term has not been extended without

the investigator's consent. We take advantage of these norms. More than 300 prisoners have

been released from the Nizhegorod SIZO. Only one went into

hiding. The others went through preliminary investigation and court as scheduled, did not

run away, lived at home, and showed up on time for questioning. Was there any point in

keeping these three hundred people in a confinement cell? No. Did their confinement have

any effect on the investigation? (Confinement is deprivation of freedom, arrest, but

instead a person should be put on bale until called to court). No. Did it have any effect

on the court? Again the answer is no. The decrees usually state, "Could go into

hiding or hinder investigation." However, these three hundred people lived at home,

did not go into hiding and did not hinder the investigation, although they were in contact

with their partners and, possibly, also with the victims. None of this had any effect on

the quality of the investigation or court procedure. Why did they have to be imprisoned?

Now let's take a look at tuberculosis. There are currently 75,000 people suffering from

open forms of tuberculosis in our country. Every year this number is increasing. If the

number of prisoners is not reduced, the cells where our prisoners are kept will continue

to be gas chambers. There is no way of separating or sorting prisoners with tuberculosis

from healthy ones. We have created a kind of incubator for breeding Koch's bacilli. And no

amount of prevention measures, no amount of new medication will help in the face of such

overcrowding.

I do not really want to go into the traditional aspects of the situation in SIZOs and colonies and the problem of malnutrition and

tuberculosis. So much has been said about them already, things have not budged an inch,

and they will not budge if another 70-80,000 people are locked away every year and if the

same investigation and judicial practice I have been talking about continues. What can we

do if 45,000 people are currently held in investigation confinement cells longer than the

terms set by the law? And if another 24,000 are not convoyed by interior troops because

they couldn't care less about transferring prisoners, they have their own problems? And if

another 60% are waiting indefinitely for their court case to be resolved?

Let's look at the measures are we currently taking to reduce the number of prisoners and

convicts. We have drawn up and sent proposals to the State Duma regarding changes in

several articles of the Russian Criminal Procedural Code. Here are some of them. We

believe that if criminal law envisages a prison sentence of no more than 8 years, any

interception measures, such as arrest, should be eliminated altogether. In this event, a

lot fewer accused persons would end up in SIZOs.

Incidentally, the current Russian Criminal Code considers such crimes petty and of no

threat to society.

At the fall session of the Duma, the question is being put forward of reducing the term

for reviewing criminal cases in the courts. This is our ongoing chronic illness. People

are registered with the court for three, four, five, six years, and no one knows when

their case will be reviewed.

Incidentally, the prosecutor's office supports us in these proposals. However, the

developers of the new draft of the Criminal Procedural Code take the following stance, why

should we patch up the old code if we are going to adopt a new code in a year or two. When

I met with them, I told them directly that they can have no idea what is going on in the SIZOs while they sit at their office desks. One month, two,

a year means nothing to them. But for the person in a SIZO

cell, one day is an awfully long time. That day may stop his health from being destroyed,

or save his life.

We also drew up a resolution draft on amnesty. There are plans to release approximately

115,000 prisoners from confinement cells and colonies. From previous amnesties, we know

that recidivism among amnestied prisoners amounts to 2-2.5%. This indicates that the

category we are releasing has already received its measure of punishment and does not pose

any threat to society. Keeping people in prison for longer than necessary is detrimental

both to the prisoner and to society.

Here we need assistance from human rights activists, public organizations and the press,

since our plans have been given the cold shoulder by the Duma. We have spoken to the Duma

factions and they do not seem to have anything in particular against resolving this

problem positively. But fall is here, and all they are concerned about is their own

political problems. Some deputies are beginning to play on the feelings of the voters,

understanding that they only have a little over a year before the elections. They recall

how they came to the Duma on the wave of the fight against crime. If they adopt our

resolution draft on amnesty now, the voters will worry that criminals will be set free and

the crime level will increase.

People who understand the problem realize that there will be no increase in crime in the

event of this amnesty. I have already mentioned that recidivism among amnestied prisoners

is minimal.

We need to expand the use of alternative types of punishment. I am proposing that our

lawyers review the articles of the criminal code, perhaps alternative punishment that does

not involve deprivation of freedom may be enough in some cases. If recidivism among

amnestied prisoners is only 2%, does it make sense to put such people behind bars?

Opponents respond that people are sent to do correctional work, but then go out and commit

crimes again. Punishment deferment is granted, but many of them still have to be

imprisoned.

Of course, there are always going to be those sentenced to alternative punishment not

involving imprisonment who will commit a crime again, there is no getting away from this.

But it is ludicrous to send so many people to prison! Our prison system is such that it is

incapable of re-educating anyone or providing anything positive. Frankly, I am very

skeptical about prison being able to re-educate anyone. At present, the only thing I want

is for us to find a way to send as few people behind bars as possible. Prison should only

be for extremely dangerous criminals who pose a real threat to society.

At present, more than 500,000 prisoners pass annually through SIZOs.

More than 700,000 are serving their terms in colonies. These are mainly middle-aged people

between the ages of 30 and 32. What does the state have to gain from pumping this number

of people through its prisons and camps? How many able-bodied men do we have? Thirty-six

million. But what kind of prospects do we have? We say that we need to build a legal

state, a market economy, create a new kind of person. But under our criminal policy, all

these people will soon be filtered through confinement cells and colonies. What kind of

market or legal state are we going to build with this type of "barracks-minded"

person who has been through prison?

Here is another important aspect. At one time we sent those accused of unpremeditated

crimes to special colony settlements. There were several of these experimental colonies in

the Soviet Union. I was in charge of one of them. We had 2,500 people of a normal

category, and there were almost no complications or problems. At the same time, these

prisoners constituted cheap labor, 2-3,000 were concentrated in one place, and they

worked. Then someone took it into his head that the punitive function of this punishment

was low. And they decided that if a prisoner was sentenced to up to five years of

imprisonment he would stay in the colony settlement, but if the term was more than five

years, he would be sent to an ordinary colony. However, there are now more than 20,000 of

those with terms of more than five years. What is the point of herding them into prisons

if the colony settlement provides harsh enough punishment for them? After all, we are

talking about people accused for the first time of unpremeditated, mainly transportation,

crimes. So what is the purpose? At present, we are putting forward the proposal that

people convicted of unpremeditated crimes should not be sent to prison, but should serve

their term only in colony settlements. And on the whole, colonies should be developed

where some of the people are not kept under guard, but can live under normal conditions

similar to those beyond prison.

We need to review the question of encouraging obedient behavior from convicts and expand

the possibilities for their provisional and early release. No one has yet measured a

prisoner's term with respect to his orientations and personal qualities. No analyst has

yet researched the problem of how long a person should spend in prison. He was given ten

years, so what. Where is the peak beyond which a person should and must be released? One

year, two years, five years? This primarily depends on his individual characteristics. But

in our country everything is terribly formalized, the time when a person is granted

provisional and early release primarily depends on the articles of the Criminal Code under

which he was convicted. The article is the main thing, and the person behind it is of

little importance. The length of a prison term is a serious question. But who is studying

this question? Criminologists in our country have nothing to say, sociologists have

nothing to say, teachers have nothing to say. But they should be made to study this

problem, to draw on their creative powers in order to change the appearance of our

prisons. If we stick to our traditional principles, we will end up with nothing to feed

our prisoners, with nothing to clothe them, and a tuberculosis epidemic beyond all

proportions.

We would like to specify the "Conception for Reorganizing the Criminal Executive

System" signed by the President. I believe that the prison block should remain part

of our criminal executive system, but it should only be for dangerous criminals, i.e. a

relatively small number of prisoners. Furthermore, there should be semi-open institutions

with vacation time, and with the opportunity to leave the prison and work during the day,

for example, while returning at night. Since 1992, restrictions have been cancelled on

correspondence, punishment in the form of depriving prisoners of packages and visiting

hours has been eliminated, and the right to make telephone calls and take vacations has

been introduced. When we came forward with this legislative initiative, we were asked if

we were in our right minds. They will all run away, they said, no one will come back from

vacation. Nothing of the sort. A few isolated cases do not return. But as a result, the

psychological climate in the colonies has changed amazingly. For six years now, people

have been leaving on vacation, their inner orientation is changing, and the attitude of

most prisoners to our system is changing. This means that we should continue in the same

direction, providing alternatives where people are less restricted by bars. We need to

think about creating institutions in which some of the prisoners are not kept under guard,

live closer to freedom and closer to normal conditions.

So we are aiming for a greatly reduced system in which, although confinement cells remain,

they are much more open than at present.

We need to create a structure for those who have received punishments not involving

imprisonment, something similar to the probation service in the West. In our country, we

sentence a person to an alternative form of punishment, and that's it, no one is

interested in him anymore. If an interest is taken there will be fewer crimes committed by

those sentenced to a provisional term, to correctional work, etc.

A rehabilitation service for released prisoners is also needed. As things stand now, a

person is released without any control or surveillance over him. Why do we not have a

service to take care of these people? If this kind of service were organized, I think it

would cost the government less that our entire system. What is more, it would provide

great advantages in the social sense.

Let's take a closer look at rehabilitation. Suppose a person has served a 5-6-8-10-year

prison term, when he is released he has lost all his social skills for adapting to the

world around him, and in addition he also has to deal with the dynamics of the current

changes in society, which is something the free person has trouble coping with. I do not

think it necessary to shut a person off from the world. After all, tomorrow the problem of

his rehabilitation will be even more serious than ever. Rehabilitation should begin from

the very first day he is under interrogation, from the very first day he spends in a SIZO.

We are also drawing up legislative proposals for the new Russian Criminal Code. New types

of punishment have appeared in this code, in particular, restriction on freedom and

arrest, which should go into effect before 2001. We propose removing these types of

punishment from the codes entirely. Restriction of freedom is essentially the same

provisional sentence with mandatory labor that used to be practiced during the Soviet era.

It was also known as "khimiya2", or "national economy building

projects." Now, despite our resistance, the developers of the new Criminal Code have

given us "Correctional Centers." These are the same "national economy

building projects," or special headquarters, but with a different name. What does it

mean today when a person convicted for the first time of a petty crime is sent to an

inter-regional correctional center, sent from the region he lives to another? He is

supposed to work there, earn a living, and feed himself. But who is waiting for him in

this other region, where is he supposed to find work? What is the point of this

punishment? Can it correct the convict, have an influence on him? Can he be deterred by

this punishment? It will result in only one thing, a person is brought to this Center,

looks around, sees there is nothing for him to do, no way to help his family, and will go

stealing for the sake of a crust of bread, or run home to his family to earn a living

there. In the first case, he will be caught and imprisoned for stealing, and in the second

for escape. The only solution is to put him in a closed zone, in prison. When I talked

with the specialists who are developing the Criminal Code, one impressive and clever

expert said to me, you are a practical worker, so you do not understand that the

punishment system should be streamlined, it is a ladder in which each step should be in

the right place. But why talk to me about a ladder? Tell me about the fate of the person

you are placing in inhuman conditions. Think about what effect this type of punishment

will have on society as a whole. Think about how this person's family will fall apart, how

work will be lost, and about how he may even be forced to commit another crime. For me,

all these clever speeches about the streamlined ladder of punishment are simply idiotic.

Nor do I see any sense in arrests. According to preliminary calculations, approximately

50-60,000 people a year will be subject to this interception measure. Let's look at what

we get. Let's say a person is subject to 6 months of arrest according to the law for the

crime he has committed, but could be given one, two, or three months. Do you know how much

time preliminary investigation and court proceedings take in our country? It will take

longer than six months to get though the investigation and court procedures. Then he is

given a verdict, essentially a SIZO term. But by this

time, he has already been under arrest for a year. So why put him in a cell, why separate

him from his family, from his normal environment, from his work? What is the purpose? To

deter him? It is impossible to deter anyone this way. It is only possible to destroy him,

mentally and physically. A cell in a SIZO or in an arrest

home is a kind of "separator" which divides those arrested into castes, some

become the dregs, others fall into the category of ordinary convicts, i.e. remain inert,

and still others become criminal authorities, i.e. become enmeshed in the criminal

environment. Prison itself can push a person of a certain character type, strong will, and

specific physical features into this category.

This is why we are in favor of eliminating these types of punishment.

I was recently asked about the draft law on control of SIZOs

and colonies by public organizations. I replied that if it is only control, I am against

it. We have so many controllers in our country at present there is no room to turn. And

then, what is there to control? We are transparent enough even now that all our problems

are plain for all to see. Experts from the Council of Europe will begin inspecting our

prisons this year. I feel positively about this. Prison should be made even more

transparent.

However, let's look at things realistically, what will change from this public control? Of

course, there will be more noise from the controllers, there will be more shouts of,

"Things are so bad . . . the budget only allots 70 kopecks per prisoner per day . .

." So, we will make some noise, we'll do some shouting, but this is not going to

increase the prisoner's rations. Times are such that shouting is not what we need, rather

we should be looking for specific solutions, working, rushing around as though there were

a fire, if you have a gaff, bring it out, if you have a bucket, run for water. But we are

not going to put out the fire by shouting and making a great fuss.

We have begun working on a conception of reform for the criminal executive system; of

course, we will need to involve human rights activists, society, and the deputies you work

with. This is constructive, it is time to stop shouting about the problems and begin

solving them instead.

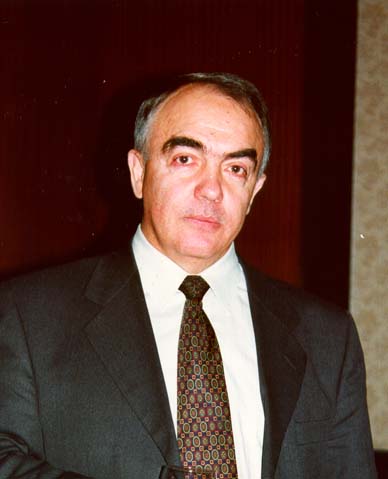

Caption to the photograph:

Yury Ivanovich Kalinin was appointed deputy justice minister responsible for the criminal

executive system at the end of July 1988. He is 52 years old. He graduated from the

Saratov Law Institute. He has worked for 27 years in the criminal executive system,

climbing the ladder from rank-and-file employee to deputy head of the main prison

department in the USSR Interior Ministry. During the 1980s he was in charge of an

experimental colony settlement for people who had committed unpremeditated crimes. (It was

a rather progressive undertaking at that time, I suggest eliminating it.) From 1992 to

1997, he was head of the Main Department of Punishment Execution of the Russian Federation

Interior Ministry. He enjoyed immense prestige among the employees of penitentiary

institutions and services. Yury Ivanovich is known to specialists in the field of

punishment execution in our country and abroad as a person who has successfully

implemented many reform ideas. His name is associated with humanization of the conditions

in our prisons and colonies.

The interview took place on August 21, 1998. This is a shortened version.

The Soviet practice of sending prisoners to serve their term at

factories and building sites around the country.